My Dad Showed Me That Legitimate Feelings Sometimes Lead to Bizarre Behavior

Re-framing an emotional event can change your response to frustrating circumstances

Editorial by Gabriella

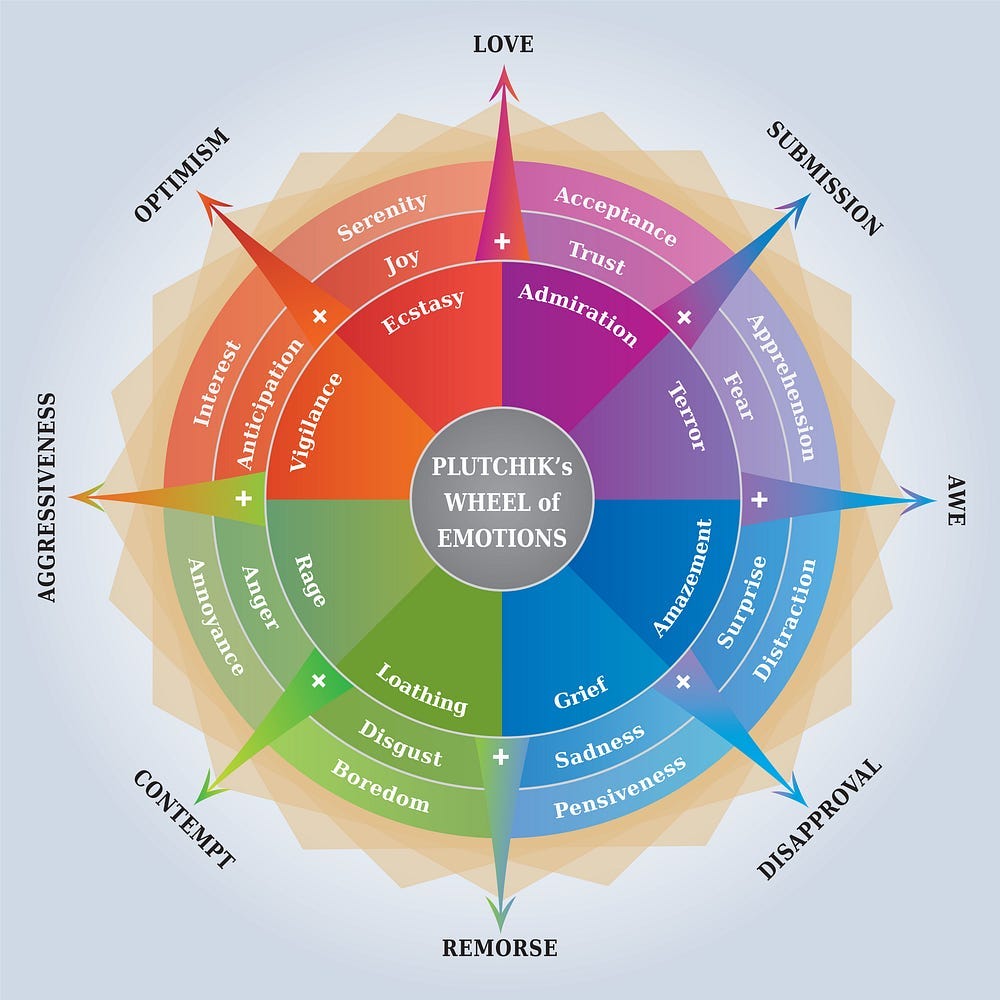

Emotions come and go throughout our lives. Just like in the image above our emotions can change at any moment. We might feel happy, angry, sad, joyful for many different reasons. Sometimes we do not know why we feel the way we do and it is good to go deep within to explore our feelings and reactions to different events in our lives. What caused us to react a certain way? Many times we can find answers within as we look closer. I am very excited to have our guest writer Chandi Challa share her exploration of emotional reactions and how answers can be found for those reactions.

This process can be different for everyone. I believe it is great to explore emotions and learn from each other’s experiences.

My Dad Showed Me That Legitimate Feelings Sometimes Lead to Bizarre Behavior

by Chandi Challa

At my parents’ house, I write in the study. If I leave the room, even for a few minutes, my dad turns off the lights.

You’re likely thinking, “What’s the big deal?”

I’ll tell you the big deal. It’s maddening!

Every time I entered the dark space, I felt enraged, irritated, and resentful.

I wasn’t just annoyed with him. The absurdity of my reaction made me deeply frustrated with myself.

Clearly, the issue wasn’t this isolated incident. My outsized emotional response pointed to something much deeper at play.

I could have easily confronted him, but I instinctively knew that he wasn’t the problem. After years of profound spiritual and psychological work, I understand that my emotions are my responsibility.

Eager to find an answer, I explored the psychological literature surrounding behavioral change. During my inquiry, I learned feelings are not the same thing as emotions. Although often conflated, they are related experiences that influence our actions in distinct ways.

It was clear I needed to address the feeling state and emotional charge to modify my response. Accordingly, I developed a methodology to reframe the situation which immediately shifted my perspective and behavior.

I’ve now made it a routine practice to use the empowering steps to take responsibility for my internal state.

While my situation is certainly peculiar, I imagine it’s not particularly unique. We’ve all experienced similar moments so I share the technique to help you with yours.

Emotions are Universal Truths

According to the American Psychological Association, emotions are bodily sensations resulting from reactions to personally significant events. They are a natural human reaction to external stimuli that transcends culture. Associated with specific psychological and behavioral changes, emotions aid survival.

For example, fear is generated when we encounter a dangerous animal. The emotion signals to our body that we are unsafe, prompting the limbic system to increase heart rate, blood flow, and breathing for a quick escape.

Clearly, emotions serve an important evolutionary function. However, their effectiveness depends on the accuracy of your emotional judgment.

Expanding on the previous example: Person A was bitten by a dog during childhood, whereas Person B has only had positive interactions. Person A is more likely to perceive a dog as a dangerous animal meaning when confronted, Person A will experience fear while Person B will not.

Same situation. Different emotions.

Therefore, healing emotional dysregulation involves addressing how you evaluate the trigger.

Feelings complicate this process because they are inextricably linked with emotions.

Feelings are Individual Perceptions

Emotions influence our minds to generate feelings and subjective thoughts based on prior beliefs and assumptions.

Essentially, emotions are a truth based on immediate, raw data while feelings are perceptions based on stories from the past.

For example, two people attend a party where they don’t know many people. Both experience a pit in their stomachs and constricted breathing indicative of an emotion. Person A, an introvert, labels the sensation as feeling awkward based on personal discomfort with strangers. Person B, an extrovert, interprets the sensation as excitement, feeling energized by the prospect of meeting new people.

Same emotion. Different feelings.

Perhaps, Person A had a traumatic social experience that was encoded as a physical emotion. Not knowing many people is a reality of the situation, and no amount of rationalization can alter that fact. However, the derived feeling of awkwardness is adjustable based on perspective.

Therefore, changing a feeling necessitates identifying and reevaluating the coinciding emotion(s). This requires exploring and reinterpreting our life experiences.

Let’s go through the framework using the seemingly benign situation with my dad.

1. Isolate the Emotion(s)

Awareness is the essential first step in the healing journey, so my first task was to label the emotion involved.

Psychologist Robert Plutchik’s well-known wheel of emotions is a commonly used tool for identifying emotions.

The middle wheel identifies the eight core emotions — joy, trust, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation. The innermost and outermost wheels represent the possible intensity ranges for each core emotion. For example, deep sadness manifests as grief while slight sadness presents as pensiveness.

The emotions displayed outside the wheel result from blending adjacent core emotions, like disgust and sadness, to generate secondary emotions such as remorse.

Sometimes, it’s easy to identify the emotion. In my case, my dad’s actions elicited perceptible rage, an extreme form of anger. However, let’s say I was unaware of my emotional state. Where the physical sensation appeared in my body provides a clue for what emotion was being triggered.

Considering I felt like punching the wall whenever he turned the lights off, it’s safe to say that my upper body reacted with symptoms of anger.

Having identified the emotion, I needed to understand what was driving the response in Step 2.

2. Identify the Adaptive Behavior(s)

According to Plutchik, the eight core emotions are predicated on distinct functions, adaptive behaviors. Identifying which adaptive behavior corresponds to the emotion reveals the true underlying issue.

For example, the adaptive behavior for fear is protection: retreating from external threat. When dealing with fear, the question to ask yourself is why is the situation perceived as an external threat?

Concerning my anger, the adaptive behavior was destruction: eliminating barriers to satisfy a need. The question I needed to ask myself was which need felt blocked?

Psychologist Abraham Maslow outlined fundamental human needs motivating human behavior in his famous hierarchy of needs:

My dad turning the lights off hindered my esteem needs harkening back to childhood. Growing up, I lived in an environment where my autonomy was stifled. My wants and desires were often overlooked, leading to feelings of confinement and disregard.

His actions reactivated those memories unleashing unexpressed anger from my early interactions. The emotion prompted my body to try and remove what I saw as a barrier to my independence.

Therefore, my issue was a sense of powerlessness.

I wasn’t mad. My childhood self was.

Having uncovered the true nature of my reaction, I was now ready to recharacterize the situation in Step 3.

3. Reframe the Event

Cognitive reframing is a psychological technique that identifies and alters how a person perceives situations, experiences, events, ideas, and emotions. According to the American Academy of Family Physicians:

“[It] focuses on changing distorted or dysfunctional thoughts in order to change negative emotions and maladaptive behaviors, as opposed to focusing exclusively on changing the behavior.”

In my situation, I exhibited several cognitive distortions:

I filtered my dad’s behavior by focusing on its negative emotional impact.

I overgeneralized by assuming the event reflected my childhood experiences.

I jumped to conclusions believing my dad’s actions were motivated by the need to overpower me.

I blamed my dad for my anger.

Once I identified the distortions, I could reexamine the incident positively and more productively.

My dad turning off the lights is a typical behavior for him. He does this almost unconsciously as he walks around the house.

Reflecting further, I realized it’s likely an ingrained response based on a 35-year-old memory of being a poor immigrant needing to save money. To him, lights in an empty room signify a higher energy bill, which was once a serious concern. For those with immigrant parents, you understand how enduring these old survival habits can be.

I suddenly felt a wave of compassion and realized his actions had nothing to do with me. He wasn’t trying to take away my freedom or devalue me. He certainly wasn’t trying to anger me intentionally. He was simply acting on a harmless, long-established habit.

It turns out, my esteem needs were not being blocked. My anger stemmed from viewing the situation narcissistically and responding from a wounded place.

It was time for the final step in the transformation process: emotional liberation.

4. Release the Feeling(s)

As I said before, feelings are mental constructs triggered by emotional responses. My anger towards my dad made me feel thoughts of irritation and frustration.

When I reframed the situation, the raw data — the lights being turned off — failed to trigger an adaptive behavior. As a result, I was able to discharge the anger completely.

Since the emotion had vanished, I no longer felt the previous feelings.

I was suddenly unfazed by his actions. Now, I simply shake my head, laugh at his quirks, and turn the lights back on.

Approaching the situation with lightheartedness brings me joy, and understanding my dad’s behavior helps me trust that his actions are non-threatening. As a result, I now feel the emotion that results from combining joy and trust on Plutchik’s wheel: love.

Next time you’re bothered, apply this approach. It’s unbelievably freeing.

P.S. Don’t worry Dad. I already turned the lights off.

Thank you for spending your valuable time with me. I am truly grateful for you, my wonderful reader.

Listen to this article here

At my parents’ house, I write in the study. If I leave the room, even for a few minutes, my dad turns off the lights.

I do that too. We call saving on our light bill or we are trying to conserve electricity. It’s reflex for me.

It is interesting how a simple action can create an emotional reaction within us. Growing up my grandmother always turned the lights off as well. electricity is expensive and when you grow up with not having much certain actions get engraved within. I don't like lights on when not needed either. I like candle light. It is comforting for me and there is no need for electricity. we are all different and our emotions and intentions are different as well. it is good to check in with ourselves why we have a certain emotional reaction and what can we do about it. Thank you for this great article.